Are Solid State Batteries Where the Industry Needs Them to Be?

Mark Fearns – Marketing at Advanced Energy Minerals

Introduction

The topic of solid-state batteries is one which excites the interest of both the scientific and public spheres

due to their potential for improved performance in vehicles, enhanced safety against conventional lithium-ion batteries and reduced environmental impact. Against the leading lithium-ion batteries of today, they

boast prospective advantages such as the reduced risk of catastrophic thermal runaway by removal of a

flammable electrolyte and significantly enhanced energy densities of over 400 Wh/ kg.

Though the liquid electrolyte battery industry has seen a meteoric rise with the development and

implementation of lithium-ion batteries, at a rate almost unprecedented in peacetimes, the solid-state

sector is yet to yield the same level of widespread commercial success despite the growing scientific and

public interest. In this issue of the AEM Newsletter, we explore where the solid-state battery status is at

and what still needs to be done before we can all enjoy safe, 1000km range vehicles.

Technological Features

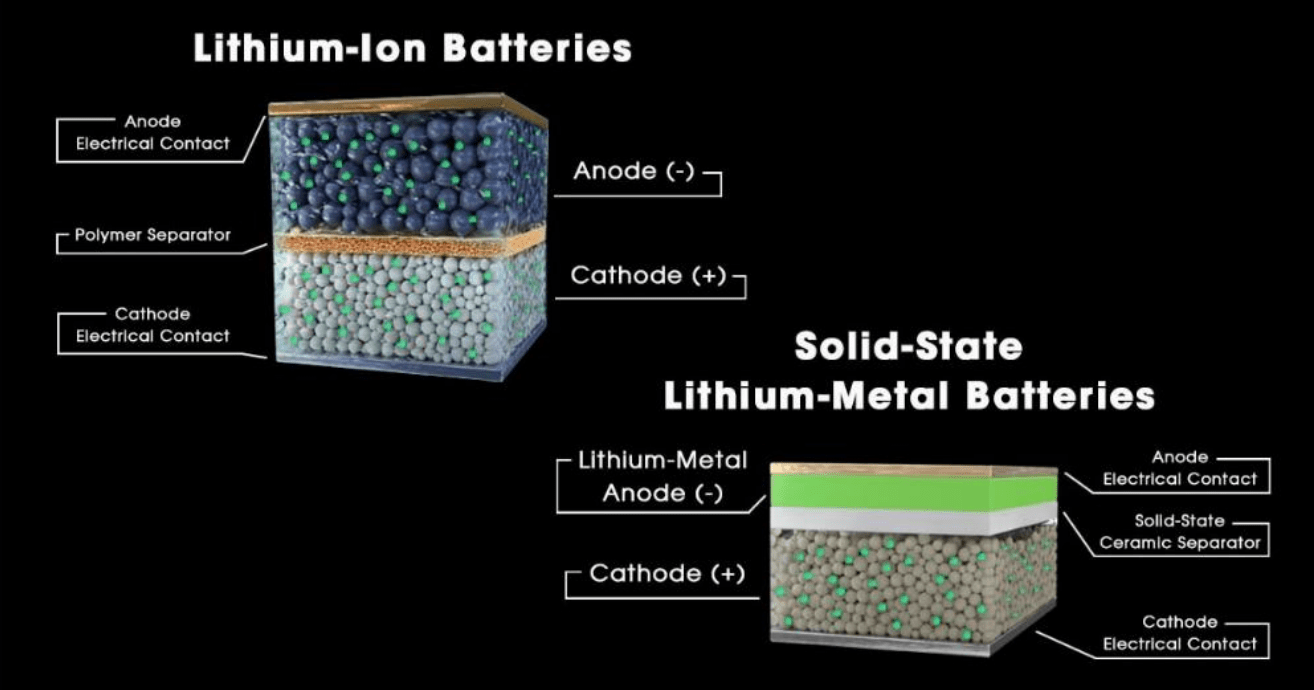

A conventional lithium-ion battery (Figure 1) is composed of a lithium-based inorganic complex as a

cathode active material (CAM), such as lithium iron phosphate (LiFPO4) or lithium oxides containing cobalt

and/or manganese; an anode typically based on graphite or silicon-carbon materials; a polymeric

separator material to regulate the ionic flow and prevent a short circuit; and an electrolyte (liquid or

polymer based) used to facilitate the flow of lithium ions.

An archetypal room-temperature solid-state battery (SSB) configuration principally differs with the

removal of the liquid phase electrolyte, instead relying on a solid or gel-like media to facilitate the flow of

ions. The solid electrolyte (SE) is found in both the cathodic component of the battery as well as the

separator, encompassing a broad variety of chemistries from ceramics to polymers, sulfides and even

halides. Interestingly, one of the most prominent anodes for SSBs is in fact, lithium metal, which is paired

with lithium nickel oxides, carbonates, and nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) complexes – such as those

developed by Prologium and QuantumScape, who target electric vehicles.

Figure 1: A diagram of a general lithium-ion battery and lithium metal SSB structure. Source: Flash® Battery srl

In SSBs the cathodic component of the battery makes up the majority of the cell volume at around 70%,

with the separator at around 10% (ideally as low as possible) and the anode making up around 20% by

volume. Contrastingly a liquid lithium-ion system contains closer to equal volumetric ratios between the

cathode and anode.

Lithium metal, sodium and silicon-based anodes show excellent promise as high-performance anodes for

fast charging and minor capacity fading, with the potential for a higher lithium-ion transference number

than liquid electrolyte systems, though both experience significant volume changes during their charge

and discharge cycles. A lithium carbon composite may provide the best balance of maintaining high

capacity and specific energy, though published research into this approach is very limited. Higher

volumetric and gravimetric capacities than carbon-based electrodes.

Challenges

The primary challenges facing present-day solid-state battery configurations are the changes in volume of

the battery components during charging and discharging, limitations in achieving the ionic conductivities

found in lithium-ion batteries and interfacial phenomena known as solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) – an

intermediary phase between electrodes which may add resistivity, worsen diffusion of ions or even

increased flammability to a solid-state battery.

Anodes and cathodes in SSBs often are faced with interfacial resistance which can give rise to unwanted

porosity, requiring sintering or coating to overcome this phenomenon. This is exacerbated by the

expansion and contraction of electrodes about the interface which further leads to raised porosity and

dendrite formation.

Lithium batteries rely on cobalt and nickel which prompts the need for sodium SSBs. Sodium runs into the

issue of having enhanced rate of cathodic degradation compared to lithium batteries, generating the

requirement for coatings on the cathode active materials (CAM) to facilitate adequate ion transport

without degrading the cathode. Further development into SEs which are more compatible with room

temperature sodium systems, such as hydroborates which have excellent electrochemical stability. Sodium

based SSBs have enjoyed notable success in the form of the molten sodium ZEBRA battery, based on

sodium nickel chloride, in addition to sodium sulfur batteries, have achieved commercial status for energy

storage applications, though have yet to achieve utilisation in electric vehicles owing to their size and

operational temperature of above 110 oC. Prominent companies include NGK and Altech Batteries.

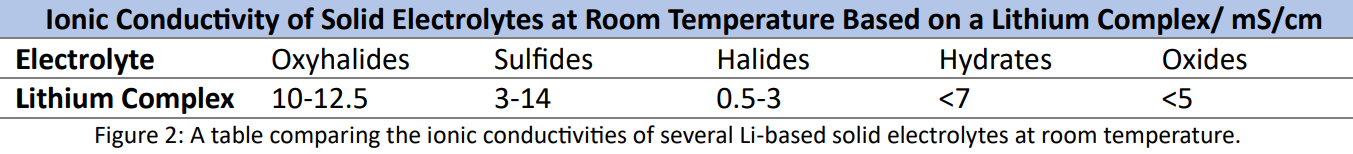

Current SSBs struggle to reliably match the ionic conductivity and diffusion kinetics achievable by liquid

electrolytes (LEs). As a reference, the ionic conductivities of lithium and sodium hexafluorophosphates in

mixture of ethylene carbonate and dimethyl carbonate is in the range of 5 – 10 mS/ cm, with 10 mS/ cm

achievable by many modern configurations. Whilst at one research team (Y. Kato et al.) reported an ionic

conductivity of 25 mS/ cm for a lithium metal system at room temperature, using a lithium germanium

phosphorous sulfide (LGPS) lithium super ionic conductor (LISICON). Significant developments into the

room temperature ionic conductivity of SEs have been made in recent times, however, particularly in the

case of lithium SEs. A publication on the use of lithium oxyhalides (Y. Tanaka et al.) (Figure 2) shows

significant promise whilst giving examples of the ionic conductivities against other Li-based SEs.

Another prominent challenge facing the commercialisation of SSBs are the effects of volumetric expansion

during operation. Solid electrolytes based on oxides may incur less expansion than sulfide-based systems,

but as indicated they generally have reduced ionic conductivity against their sulfide counterparts. The risk

of volumetric expansion, and thus destruction of the battery cell, is often mitigated in lab conditions by

applying linear pressure to maintain the structure of the cell; a procedure not feasible in the event of fullscale commercialisation of this technology particularly if the target application is electric vehicles. The

requirements for stack pressure therefore present a serious design consideration for the manufacturers of

sulfide-based SEs.

Similarly with regards to the change from liquid electrolytes to solid, the porosity of the cathode is of

paramount importance. A cathode which has a very high packing density of cathode active materials

(CAMs) will in theory have a higher energy density, though it will suffer tortuosity in the transport of ions

generating a bottleneck and impeding ionic flow. This will require pore optimisation or may demand the

need for an even more conductive solid electrolyte. If the cathode is too porous then the energy density

of the cell will decrease and may cease to be competitive.

Safety

Solid-state batteries are heralded as a safter option to lithium-ion batteries in the public sphere. The

removal of a flammable electrolyte, typically composed of an organic solvent, does offer the possibility of

reduced risk of thermal runaway effects, though a full assessment of the safety of SSBs is not yet fully

developed.

Solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) may have a reduced level of diffusivity in a solid system due to solid

kinetics. The flammability of such SEI phenomena must still be investigated, though in one case a research

team experienced the ignition of a lithium aluminium germanium phosphate (LAGPO) species at 200 oC

about the interface between the SE and the lithium metal anode, despite being under inert conditions in

a glove box.

Dendrite formation has been previously described as an unwanted phenomenon in battery configurations.

From a health and safety perspective, the dendrites are newly exposed areas of anode which propagate

beyond their intended volume and, in effect, may exponentially raise the rate of reaction of the

electrochemical processed within a battery, generating heat and eventually thermal runaway.

Incompatibilities between the separator and the anode may raise porosity about the solid electrolyte

interphase which can provide a platform for dendrite growth to form if not properly mitigated. Sintering

of ceramic-based SEs is a measure taken to alleviate the risk of dendrite growth about the SEI, however,

this raises production cost in large scale implementation.

Towards the Future

The development of battery technology has been groundbreaking in the past 20 years. Lithium-ion systems

have now achieved full commercialisation and show no signs of slowing down, barring legislative or

industrial mining changes. Solid state batteries present the next pass of the baton in the promethean

development of sustainable, high power energy systems. SSBs have also made significant developmental

progress, and show excellent promise even against LIB systems, though to achieve the same level of

commercialisation, further development is needed based on publicly available information.

Ensuring high ionic conductivity is one of the primary challenges facing SSBs. Alternative materials,

processing, and coating technologies (alumina, ceramics) may help improve ionic conductivity without

raising electrical conductivity, with even greater benefits if they can mitigate unwanted SEI effects.

Lithium anodes are currently the highest performing in terms of energy density under room temperature

operation, but the dendrite formation and inherent flammability of the metal are challenges in their own

right. Further development into hybrid anodes or the use of silica and carbon may help improve in this

regard.

Ensuring a competitive packing density of cathode active materials will be a challenge for the industry as

it strives to compete with itself.

The solid-state battery market is not where it needs to be today, but it may exceed where it needs to be

in the near future.